March 31, 2025 marks the 94th anniversary of the plane crash that claimed the life of my great-grandfather, Knute Rockne, and seven other men.

On March 31, 1931, Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne was scheduled to fly on T&WA’s 8:30 a.m. flight from Kansas City to Los Angeles. The morning sky was overcast, a light misting rain fell, and a delayed mail shipment held up the plane’s departure. Piloting the Fokker F-10A aircraft was former Marine Corps pilot Robert G. Fry and co-pilot Herman “Jess” Mathias. Among the five other passengers were H.J. Christen, an interior designer on his way to visit his wife in California; C.A. Robrecht, a produce merchant taking his first flight; Waldo B. Miller, an insurance salesman on a business trip; Spencer Goldthwaite, a 25-year-old traveling to Pasadena to visit his parents; and John Happer, a controller at the Wilson-Western Sporting Goods Company and a friend of Rockne’s.

When the delayed mail finally arrived, the flight left Kansas City at 9:15am and was uneventful until 10:22am, when it encountered bad weather. Co-pilot Jess Mathias radioed in, reporting that they were flying low and requesting the weather conditions in Wichita. After being informed of clear weather ahead, Mathias responded that they would try again and divert to Olpe if necessary. At 10:45 a.m., the co-pilot made another weather request. When the radio operator asked, “Do you think you will make it?” Mathias’ last transmission was, “Don’t know yet, don’t know yet.”

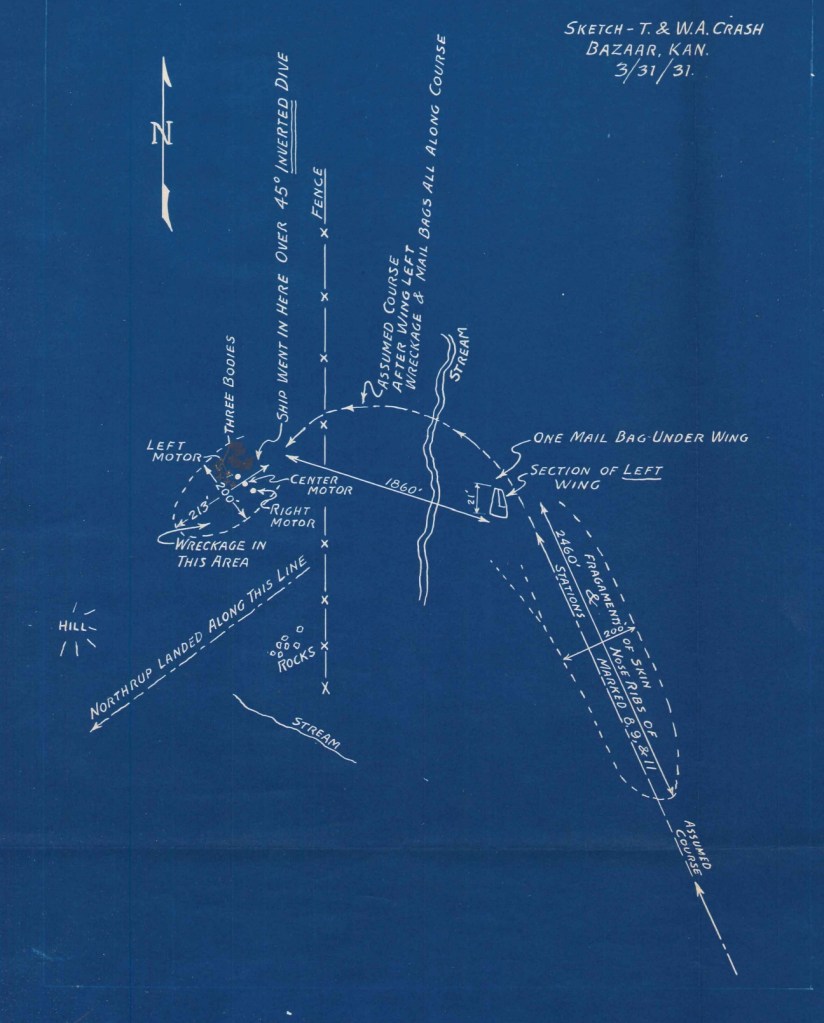

The plane crashed violently, driving its engines deep into the earth. Remarkably, the tail remained intact while the left wooden wing, which had detached mid-flight, was found three-quarters of a mile from the fuselage. The site was unsecured before official investigators arrived later that day. As news of the wreck spread, souvenir hunters swarmed the area, with over one hundred cars lining the nearby road by the afternoon. Pieces of the aircraft that may have provided clues about the cause of the crash were taken, along with anything else that was loose at the scene. When investigators did arrive, they found very little to work with.

The investigation uncovered conflicting evidence. NAT pilot Paul E. Johnson, who took off behind the doomed flight, encountered bad weather and ice accumulation but managed to reach Wichita. It was theorized that ice had formed on the plane, as mechanic L.E. Mann claimed to have seen U-shaped ice near the wing, while eyewitnesses Edward Baker and RZ Blackburn reported seeing no ice at the crash site. Pilot Robert G. Fry was regarded as highly skilled, yet aircraft designer Anthony Fokker, after examining the wreck, attributed the crash to severe weather, pilot error, and failure to follow cargo regulations. Pilots who had flown the Fokker F-10A admitted fearing the aircraft due to its tendency to experience severe wing flutter.

Before this accident, the Department of Commerce’s Aeronautics Branch kept accident investigations confidential. However, the involvement of a high-profile passenger sparked public interest and demands for transparency. The investigation was poorly handled, with officials initially presenting one theory, only to revise it as new evidence emerged. Though officials never agreed on an official cause, it is believed today that the left wing of the aircraft, while flying in bad weather, experienced a structural failure due to accumulated internal moisture that had weakened the glued joints.

The lack of wreckage, conflicting evidence, and the Department of Commerce’s mishandling of the investigation incited conspiracy theories about the crash’s cause. Just weeks after the tragedy, a booklet suggesting foul play appeared on newsstands, only to be pulled following public outcry.

Then, on January 6, 1933, the South Bend News-Times published a report claiming to have learned “from an unimpeachable source” that the 1931 airplane crash was caused by a bomb, intended for Father Reynolds, a history professor at Notre Dame, in retaliation for his testimony in the Jake Lingle case. According to the item, the Secret Service had identified a man who had hidden the bomb in a mail pouch carried by the plane.

The story was picked up by newspapers across the country, but major publications like The New York Times chose not to publish it. No arrests were ever made, and several newspapers later ran articles debunking the claim. Even Father Reynolds dismissed the story, telling the South Bend Tribune, “There was no possibility of my taking the plane, and the story is ridiculous.”

But the story endured, fueled by Father Reynolds himself. Notre Dame alumnus James Bacon recounted a 1934 conversation with Reynolds in his 1977 book Made in Hollywood. According to Bacon, Reynolds encountered Rockne on the Notre Dame campus, where Rockne expressed frustration over being unable to secure a last-minute plane ticket to Los Angeles for a meeting with Universal Pictures. Reynolds, who had a ticket from Kansas City to Los Angeles that he couldn’t use, offered it to Rockne, which he accepted.

Father Reynolds told us:

‘My name was on Rock’s tickets and reservation. He didn’t have time to change them. And then all those threats on my life. Did those people plant a bomb on that plane for me? I don’t know. I know if I hadn’t given Rock my tickets, he would have been alive.’ (Made in Hollywood, p. 205)

By 1986, Reynolds had altered his story. In an interview with journalist Ron Karten, he no longer claimed to be the intended target, rather, the mob had directed its retaliation at Rockne for his testimony.

The story evolved into an urban legend, resurfacing every so often in the press as an oddity. In 2013, Tom Ley of Deadspin wrote of the conspiracy theory and pointed out the inconsistencies in Father Reynolds’ account. However, in 2019, investigative reporter Jeff Harrell published an article in ND Magazine, countering there was evidence to support the theory. He later expanded his article into two books on the subject.

So, is it true?

In 2024, I began collecting primary source materials on my great-grandfather, Knute Rockne, with the intention of creating a family archive. One document I struggled to track down was the official crash investigation report done by the Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce.

My search began at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in College Park, MD, which houses the records of the Aeronautics Branch. However, I was informed that the air crash investigations from that era had been disposed of, a statement also noted on NARA’s webpage under the Records of the Federal Aviation Administration section. Determined to find it, I expanded my search to other archival institutions, hoping another copy existed elsewhere.

While I found references to documents held in a “Rockne Crash File” at the National Air and Space Museum in Marc Dierikx’s 1997 biography on Fokker, it was an archivist at Embry-Riddle who provided a more concrete lead: a citation explicitly listing an “Accident Report” within the same “Rockne Crash File.” I reached out to NASM, but after a lengthy wait, the archivist informed me that they were unsure of its whereabouts, though they continue to search for it today.

While waiting to hear back from NASM, I followed another lead: a reference to a photocopy file of the report held at the United States National Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson. Unfortunately, the museum confirmed the report was no longer in their possession, with no accession or deaccession record. This isn’t necessarily suspicious, as photocopies may not have been recorded if the originals were held elsewhere.

But all was not lost. In 1966, an aviation author, Rick S. Allen visited the USNAFM and made detailed notes that contained excerpts from the 147 documents contained in the file, some of which were once classified. This document he created was later published in the 1986 Fall issue of the American Aviation Historical Society Journal under the title “More on the Fokker F-10A.” You can access the original copy of Rick S. Allen’s notes here, and it can also be found in the Richard K. Smith Papers at Auburn University, the Ona Gieschen Papers at the State Historical Society of Missouri, and at the Chase County Historical Society.

In addition to Allen’s notes, I collected numerous primary source materials, including newspaper clippings and photographs. From this collection, I was able to trace many of the falsehoods surrounding the crash, the conspiracy theory claims, and solve the mystery surrounding the flight ticket.

Flight 599 or Flight 5?

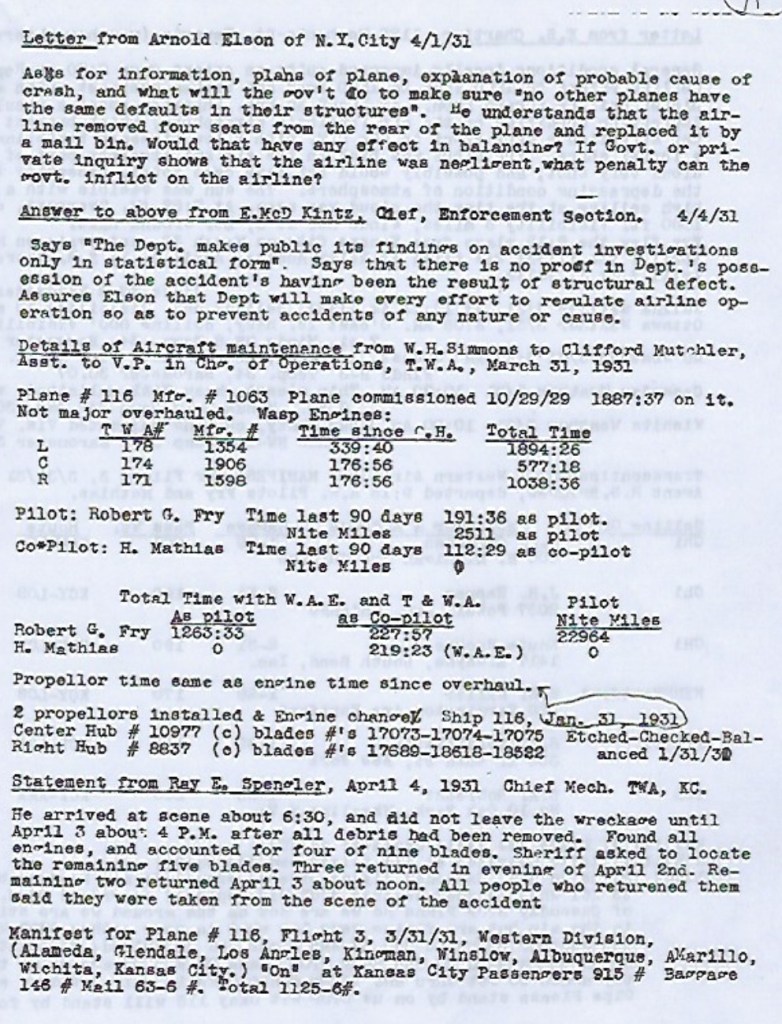

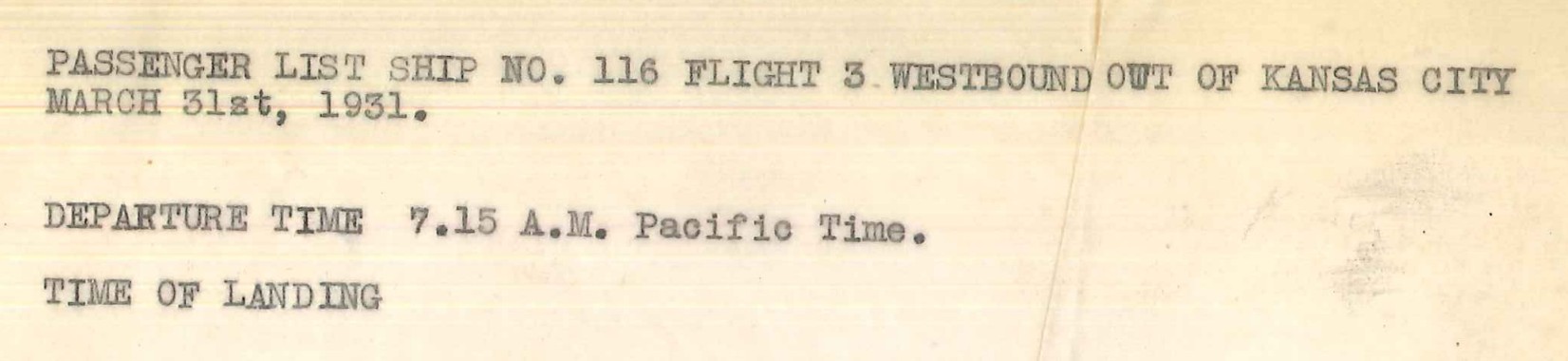

For the past 94 years, this flight has commonly been referred to as either Flight 5 or Flight 599. Both numbers are incorrect. The correct designation is Flight 3. Dominick Pisano, curator at the National Air and Space Museum, and Ona Gieschen, former TWA flight attendant and historian, both of whom had access to primary source documents, used Flight 3 in their publications, and Rick S. Allen’s notes also list Flight 3 in the flight manifest. It is also the number on the Passenger List found in the TWA Incident file on the crash, held in the TWA Records at the State Historical Society of Missouri.

A TWA timetable from February 1, 1931, confirms Flight 3 as the correct schedule, while an April 20, 1931, timetable assigns the route and schedule to Flight 5—likely the source of the confusion.

Rockne Died in a Kansas Wheat Field

Rockne’s plane crashed in the Flint Hills of Kansas, a region known for its rolling hills and prairie grass. It wasn’t a wheat field, but a pasture.

Jack Frye’s Whereabouts

Douglas J. Ingells’ 1966 book, “The Plane that Changed the World,” about the Douglas DC-3 aircraft, opens with a dramatic scene: Jack Frye, V.P. of T&WA, at the Kansas City airport on the morning of March 31, 1931, anxiously checking his watch as he awaits the departure of Flight 3, then observing its late takeoff. Whether Frye told this to Ingells or Ingells fabricated it to add an emotional layer to the story of the Douglas DC-3 aircraft, I don’t know. But Jack Frye was not at the Kansas City Airport on that day.

On page 18 of the Coroner’s Inquest, obtained from the Chase County Historical Society, the examiner asks Frye to explain why the left wing may have snapped off. Frye responds:

No sir. I have no opinion as to that. As I say I left Los Angeles late yesterday afternoon and just arrived late this morning and have had no chance to make any study of the ship or the reports.

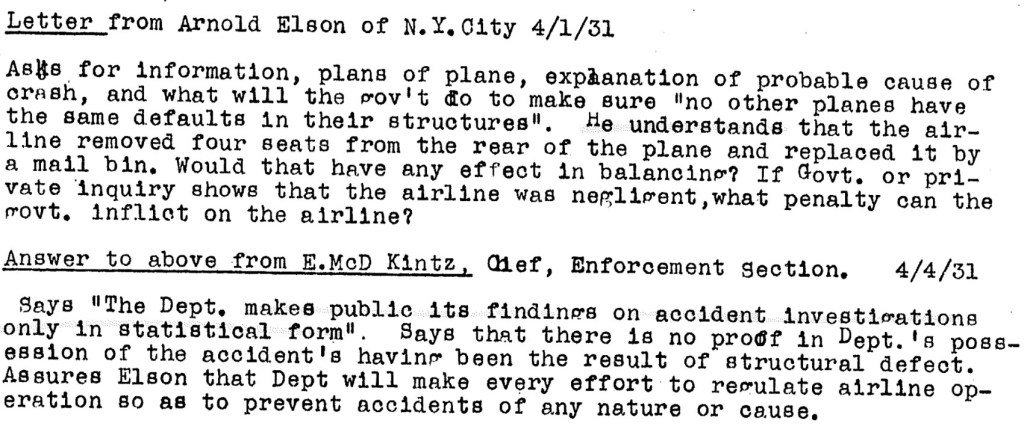

Four Passenger Seats Were Removed to Make Room for the Mail

This claim has appeared in recent publications, but it doesn’t hold up under scrutiny. The Fokker F-10A was equipped with designated cargo compartments, so there was no need to store mail with the passengers. Allen’s notes confirm the mail was stored in the front compartment of the plane, near the pilot.

So, where does the claim about four removed seats come from? I found no mention of it in any of the primary source documents I collected, nor in any of the historical news articles I reviewed. However, it does appear in Allen’s notes on page 11, in a letter. Here’s what it says:

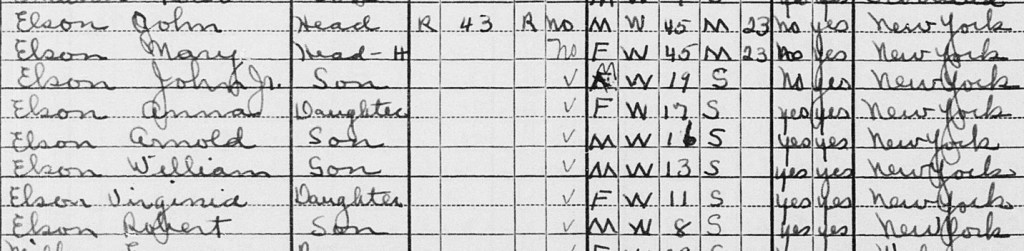

Allen was very diligent, and when he wrote down people’s names, he made sure to include their title. Except Arnold Elson doesn’t have a title. A search for Elson yielded no results in government or corporate records from the timeframe and the New York City area, but I did find him in the 1930 Census of Brooklyn, New York.

The record lists him as a sixteen year old with Norwegian and Swedish grandparents. He also appears in a newspaper article from the Brooklyn Eagle, dated March 4, 1932, which reports that he won first prize in four events at the Norwegian Turn Society junior meet.

While I can’t confirm this is the same Arnold Elson without the original letter and address, the canned response from E. McD Kintz and the census record suggests he was a curious teenager who wrote to the Department of Commerce for more information about the aircraft and crash.

Eyewitnesses Saw Flames and Heard an Explosion

The clouds were low that morning, hovering at around 500 feet. Eyewitnesses did not see the plane until it emerged from the clouds, by which point the wing had already separated from the fuselage. They recalled hearing the pilot shut off the engine, followed by backfiring. When investigators examined the throttles, they found them closed.

At the Coroner’s Inquest held on April 1, 1931, Edward Baker testified:

Just noticed a plane, and then I noticed it seemed to be kind of spluttering or the engine wasn’t working just right or perhaps it was backfiring and then it seemed to be quiet a little while and I didn’t hear anything. Then I heard the crash, I suppose when it hit the ground. I thought at that time it was an explosion.

His father, S.H. Baker, told the Associated Press:

Quite a few people heard the plane’s engine missing and the crash– like a mild explosion from a mile away. They were so excited they told different stories about how it sounded.

E.G. Edgerton, manager at T&WA, was quoted in the Decatur Evening Herald on April 1, 1931, saying:

The wreckage was soaked with gasoline, proving there was neither an explosion nor a trace of fire aboard the ship

L.E. Mann also testified at the Coroner’s Inquest:

Yes, there was gasoline and one mail sack was saturated with it.

The Emporia Weekly Gazette, April 9, 1931, had this to say about the reporting that was done on that day:

Who can say that the muse is dead in Kansas as long as the Wichita Beacon’s rewrite department maintains the high stride of imaginative and creative writing it took in the Rockne crash?

The rest of us poor, plodding, uninspired worms, after viewing the fallen plane, retired to our typewriters and wrote a story mildly marveling that the wreckage did not catch fire, in view of the fact that spilled gasoline must have drenched the hot motors.

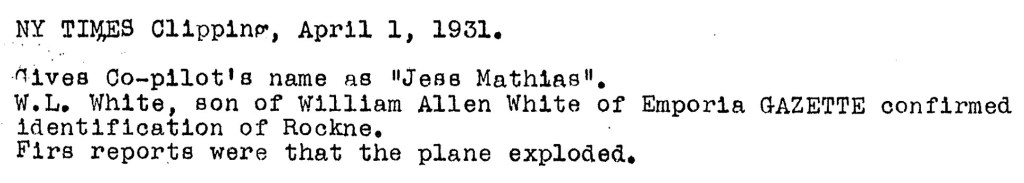

The Official Department of Commerce Investigation Report says “First reports were that the plane exploded.”

There’s no way to verify that without the actual report, but this exact sentence appears in Allen’s notes on page 15, as a entry for an NY Times clipping.

Eyewitnesses Were Coerced Into Changing Their Testimony

In the past 94 years, no eyewitness has ever suggested that anything like that happened. Though none of them are alive today, no relatives or anyone else have ever claimed otherwise.

$55,000 Went Missing at the Crash Site

One of the passengers, H.J. Christen, was reported to be carrying $55,000 on the flight, but it was later located in a safety deposit box.

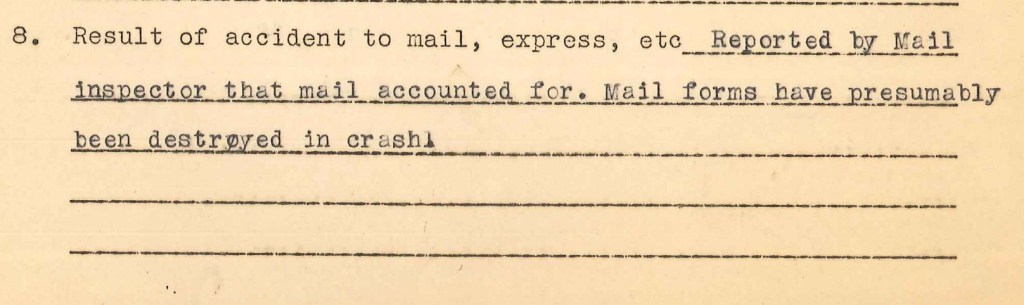

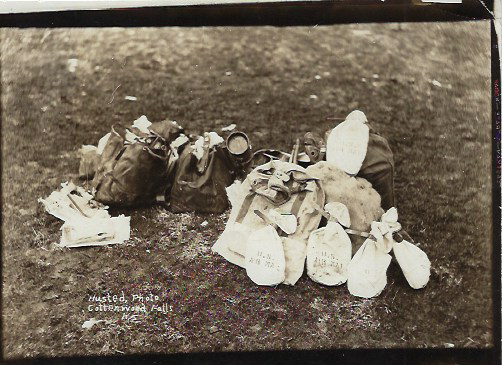

The Bomb was in a Mail Sack

According to the Form #151 in the TWA Incident file at SHSMO, all mail was accounted for. The T&WA Traffic Department’s accident report also confirmed that while one registered pouch had its lock broken off, every pouch was recovered.

Mail sacks were found strewn around the wreckage, which led investigators to surmise the wing had fallen straight down and “a mail bag was found under this broken wing, which may have fallen out when the wrench opened the mail compartment door.”

Anthony Fokker Inspected the Plane Himself and Found Nothing Wrong

Fokker claimed to have inspected the plane in Amarillo, TX on March 28 and found no problems. When he was at the scene of the crash, he examined a wing fragment, but his findings differed from those of another investigator. Fokker arrived at the scene on April 2, and Allen’s notes recorded his findings:

Picked up a piece that was left (wing had been removed), part of the bottom flange of the front spar, which showed a break under tension. Material and glue joints all perfect.

He later concluded the wing had failed due to excessive overstraining.

However, Leonard Jurden, Supervising Aeronautical Inspector for the Department of Commerce in Kansas City, found evidence of structural faults in the wing. In a letter to the Chief Inspection Service he wrote:

Examination of these parts showed that in the upper and lower laminated portions of the box spar, some places the glued joints broke loose very clean, showing no cohesion of the pieces of wood. Other places showed that the glue joints were satisfactory. Two pieces, showing definite compression breaks as well as poor glueing, and another taken from the broken end of the broken wing are being expressed to you.

The F-10A wings were the first to be manufactured in the US at the Fokker factory in Glen Dale, West Virginia, whereas the F-10 had Dutch-made wings. Finding skilled workers in the Glen Dale area who could meet the exceptionally high standards required for maintaining the structural integrity of the wing proved challenging for the Fokker company. Additionally, the Fokker F-10A featured a wider wingspan than the F-10. This increased wingspan made the aircraft more susceptible to flutter, which increased the amount of stress placed on the wing.

This was not Fokker’s first rodeo with structurally unsound wings. During World War I, his Dr.I aircraft–the aircraft flown by the Red Baron– was grounded due to wing failures caused by poor workmanship.

A Mechanic Refused to Sign Off On the Plane Right Before Takeoff

The story of T&WA mechanic, E.C. “Red” Long refusing to sign off the plane appears in recent publications, but a key detail is often omitted, making the account misleading: Long didn’t work at the Kansas City Airport. According to a 1986 article from the Hickory Daily Record, “He inspected the plane in Alhambra, Calif., when he was working for Western Air Express.”

This means he could not have inspected it immediately before its March 31 departure from Kansas City.

It’s unclear from Long’s interview when exactly he inspected the plane, but gives the year as 1931. NC999E, the plane’s registration number, was previously owned by Western Air Express before the merger with Transcontinental Air Transport to form T&WA. It flew the Los Angeles – Agua Caliente Route from 1929 through at least early 1930. A T&WA timetable from February 1, 1931, includes both Alhambra and Glendale airports for Flight 3 Los Angeles arrivals, and this news article states T&WA moved to the Glendale Airport on March 15, 1931. As a point of interest, the plane had logged 1251 hours 49 minutes when it was transferred to T&WA during the merger and 1887 hours 37 minutes when it crashed.

Determining a date of Long’s inspection will require further archival research, but using the documents I’ve gathered so far, I was able to trace the aircraft’s activity leading up to March 31, 1931.

The TWA Incident file contains a letter from Art Bodine, Field Manager at Kansas City, to Paul Richter, vice president of T&WA Western Addition. In it, Bodine states that ship #116 arrived in Kansas City on March 28 from its scheduled Los Angeles flight at 7:59pm. The aircraft was inspected on March 29th, found to be in first class condition, and remained in the hangar until the morning of March 31.

Using the digitized register of the Grand Central Air Terminal, also known as the Glendale Airport, records show that NC999E departed Los Angeles on March 26 at 5:03 am with 9 passengers. It would have arrived in Kansas City at around 8 p.m..

However, on March 26th, the western United States experienced extreme blizzards and storms, which grounded many planes. According to a report from the Albuquerque Journal on Friday, March 27, the storm disrupted T&WA flights on Thursday, March 26, causing the eastbound plane to be held at Winslow, Arizona.

Anthony Fokker claimed he personally inspected the plane in Amarillo on March 28, three days before the accident. A brief news piece in the San Angelo Standard Times (March 29 edition) reported that Fokker arrived in Amarillo on the morning of March 28 and departed at 1:43 p.m. The plane’s regular LA-Kansas City schedule had it arriving in Amarillo at 3:45 p.m. and departing at 3:55 p.m., meaning it must have arrived earlier for Fokker to examine it, unless the news report was inaccurate or Fokker was not truthful.

The Grand Central Air Terminal register also recorded NC999E arriving in Los Angeles on March 23. Unfortunately, the pages for March 24 and March 25 are missing. But from what we have, the aircraft’s movements between March 23 to March 31 can be reconstructed as follows:

March 23 – Kansas City – Los Angeles

March 24 – unknown

March 25 – unknown

March 26 – Los Angeles – Winslow, AZ

March 27 – Unknown

March 28 – Amarillo, TX – Kansas City

March 29 – Kansas City Hangar

March 30 – Kansas City Hangar

March 31 – Day of crash

This indicates that the aircraft completed at least one round trip in the week before the crash, during which it encountered bad weather.

If you are wondering why Pilot Fry’s name does not appear in the register, it’s because pilots did not fly the entire route to Los Angeles. Instead, pilots from Kansas City flew as far as Albuquerque, where another pilot took over for the remainder of the journey.

As for the inspections, Jack Frye described the process in his testimony at the Coroner’s Inquest. Aircraft undergo inspections after every flight and before every departure, with major inspections conducted every 28 hours. Different parts are inspected at varying intervals, and both the pilot and copilot perform a pre-flight inspection.

Rockne Couldn’t Find a Plane Reservation

The theory that Rockne used Reynolds’ ticket is rooted in the idea that he was unable to secure a flight reservation. The Fokker F-10A could seat 12 passengers, yet only 6 were aboard that day, meaning the flight was far from full. For Rockne to have been unable to book passage, T&WA would have had to be limiting seating to half capacity, which seems unlikely, and the same plane carried 9 passengers on March 26. While one could engage in mental gymnastics and suggest that perhaps six other passengers cancelled that day, this scenario is also highly improbable. Given that 1931 was at the peak of the Depression, and plane tickets were expensive (a trip from Kansas City to LA cost $120, equivalent to $2,519.07 today), the idea that six passengers cancelled or seats were unavailable seems far-fetched. T&WA’s goal was to fill seats, making it unlikely that booking a ticket would have been a challenge.

Whose Name Was On the Ticket?

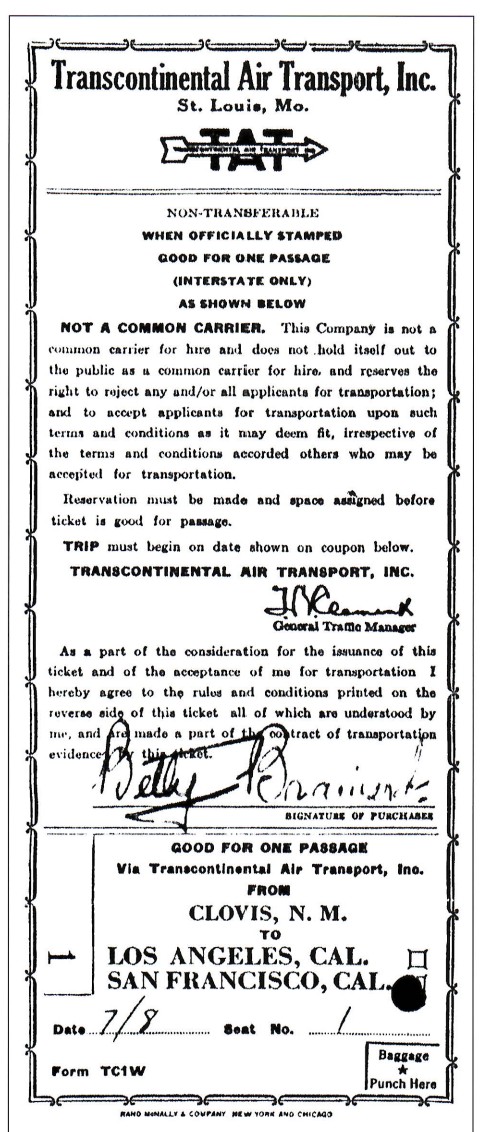

Father Reynolds initially claimed his name was on the ticket, while proponents of the conspiracy theory argue that the ticket was transferred over into Rockne’s name. So, which is correct?

Before the bodies were officially identified, the airline released a copy of the passenger list to the press. I found no evidence that Father Reynolds was mistakenly reported as being on the aircraft.

During the Coroner’s Inquest, county attorney H.C. O’Reilly presented the passenger tickets and list found with the pilot as evidence. He questioned T&WA ticket agent R.S. Bridges about a discrepancy between the passenger list and the name on one of the tickets. Specifically, one ticket bore the name of Mrs. S. Goldthwaite, while the list records only S. Goldthwaite. Bridges explained that ticket agents typically wrote in passenger names, suggesting the inconsistency was likely an error by the seller or, if filled out by the passenger, a mistake on their part. Since Spencer Goldthwaite was unmarried, this was an error by the ticket agent, not an instance of Goldthwaite using his wife’s ticket. If Rockne’s ticket had listed another name, it would have been brought to the jury’s attention.

As was the case then and remains true today, the name on an airline ticket constituted a contractual agreement. One clause in T&WA’s ticket contract stated that the airline bore no liability in the event of an accident. If a passenger’s name was not the correct one on a ticket, it could expose the company to lawsuits, or, for the passenger, an inability to collect on an insurance claim.

Furthermore, tickets were non-transferable. Allowing transfers would result in lost ticket sales for T&WA. This means Father Reynolds’ ticket could not have been transferred to Rockne.

The True Story Behind Rockne’s Ticket

Rick S. Allen recorded a copy of the flight manifest for Flight 3, which shows that both Rockne’s and John Happer’s tickets were purchased at the Chicago office. Happer, a friend of Rockne, worked for Wilson-Western Sporting Goods, for which Rockne was a spokesperson. The two were traveling to Los Angeles together.

The South Bend Tribune reported on April 1, 1931:

Only a trick of fate prevented Dick Hanley, Northwestern university football coach, from making the trip. Hanley had been invited by Happer, but refused because of his wife’s illness.

Happer, who was killed in the crash, accompanied Rockne on the trip by rail from Chicago to Kansas City, Mo., and they boarded the plane together. All arrangements for the flight were made by Happer, who intended to visit his brother, Ralph Happer, manager of the San Francisco branch of the Wilson company, while on the west coast. Rockne was to have made movie “shorts” in Hollywood on spring football practice.

Christy Walsh, head of a feature publishing syndicated and long-standing friend of Rockne, also had been invited to accompany the travelers, but decided to remain in South Bend until Rockne returned.

Conclusion

As usual, the truth is much more interesting than fabrications. The tragic event of March 31, 1931, was the result of multiple factors converging on that fateful morning.

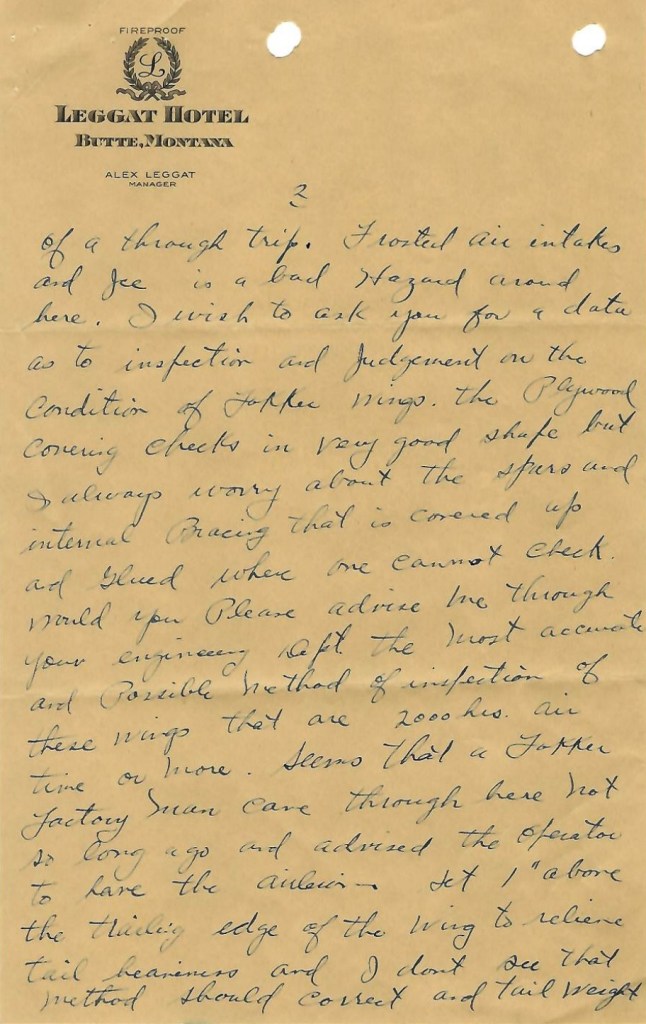

The wooden wings of the Fokker F-10A were constructed in a way that made inspections difficult, with the plywood skin of the wing needing to be removed in order to check inside. Concerns about the wing were brought to the Department of Commerce’s attention in late 1930, when a National Parks Airway inspector wrote about the inability to check the spars and bracing inside. Prior to the crash, the U.S. Navy tested the aircraft twice for potential use but rejected it both times due to instability.

The Aeronautics Branch examined the Fokker F-10A, and by March 30, 1931, they felt they had enough evidence to justify grounding the aircraft on April 1. Interviews conducted with pilots during the crash investigation cemented their concerns. In a confidential letter dated April 8, Leonard Jurden wrote to Gilbert G. Budwig:

Jim Kinney and I received our first definite information that Fokker F-10, particularly the long-winged job, do set up a decided flutter in the wing when the normal cruising speed is slightly increased and bumpy air encountered.

For reasons unknown, the Department of Commerce didn’t ground the aircraft until May 4.

The planes were eventually allowed to return to service after the airlines agreed to regularly inspect the interior of the U.S.-made Fokker wings. The inspection process involved removing, then reinstalling the plywood skin, which proved to be expensive and labor-intensive. The high cost, combined with the public’s loss of confidence in wooden-winged aircraft, rendered the aircrafts virtually worthless. By 1934, T&WA had salvaged the engines and burned their Fokker F-10As, along with the ill-fated Fokker F-32. Anthony Fokker was driven out of the US aviation market and returned to the Netherlands.

In 1931, the commercial aviation industry and the U.S. government had a close, largely unregulated relationship. Both were eager to promote commercial air travel and the Department of Commerce withheld the causes of aircraft crashes to avoid discouraging the public from flying. However, this crash changed that dynamic, and led to significant reforms. New laws gave the Department the ability to subpoena witnesses in investigations, secured wreckage sites, forbade the removal of evidence from the scene, and barred government officials from publicly speculating on the causes of accidents before an official cause had been determined.

Although wood was already being pushed out of aircraft design, the crash accelerated the shift to all-metal construction and played a key role in the development of the Douglas DC-3, an influential aircraft in aviation history.

It is my opinion that if the Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce, the Fokker company, or T&WA had found the slightest evidence of a bomb or foul play, they would have seized on it immediately to deflect blame and avoid repercussions. A targeted bombing is a one-time event, but a structural failure occurring across a number of planes is far more damaging, both financially for airlines and aircraft designers, and psychologically for the flying public.

A complete bibliography for this piece, along with a list of archives that contain materials related to this event, can be found here.

A sincere thank you to the late Rick S. Allen. Without his meticulous notes, we would know so very little about the government investigation.

A heartfelt thank you to the Chase County Historical Society and the State Historical Society of Missouri. These invaluable archival institutions preserve many primary source materials about the crash and were incredibly helpful in providing access to their collections. If you’d like to support the preservation of this historic event’s legacy, please consider donating to one or both of these organizations.

I am grateful to the following organizations for providing access to their collections. Even when resources were unavailable, individuals at these organizations were exceptionally helpful and guided me toward valuable leads.

The American Aviation Historical Society, Auburn University, The TWA Museum, Kansas Aviation Museum, Embry-Riddle Archives, The National Air and Space Museum, The National Archives and Records Administration, and The American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming.

Leave a comment